To a teen stuck between rock’s first glorious age and its second revolutionary one, Talking Heads were the anchor. Talking Heads may have been the polar intellectual opposite of the Ramones (from qu’est-ce que c’est to “Gabba Gabba Hey”), but they were playing on the same new team: a New York farm franchise that set up training camp in the dive club where hippie Bleecker Street ended and the dire Bowery began.

A golden age of alternative music was about to be born, very much cast in the image of Talking Heads, but through a process that followed a parallel course with the band’s career. The peril of growing up in New York in the Seventies was having the city’s ailing condition constantly held up to the impossible standard of our parents’ fond recollection of the Forties and Fifties. Through their rosy rear view it seemed that the world was one big hot fudge sundae, with dapper fellows in sport coats and cardigans sweeping bobby-soxed gals off their feet in the dance halls and arcades of Coney Island, Roseland, and other long abandoned venues.

Denigrated ’70s New York smeared grime over this former glitter. The once idyllic subway rides to the outer boroughs were now suffocated by graffiti and the movie date devolved from “Guys And Dolls” to “The Taking Of Pelham 123.”

At one time, Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra, and Judy Garland sang, “I’ll take Manhattan, the Bronx, and Staten Island too.” But the benign world of Rodgers and Hart’s song was now rotten. In its place was a forsaken dystopia with a hot soundtrack—the rumbles of punk against the steady heartbeat of disco. It was a dynamic tension that stretched as tight as a rubber band in the sweltering summer of 1977, when New York nearly melted.

Out of radios came the insinuation of a bass riff, and the odd, dispassionate voice of a man about to snap: “I can’t seem to face up to the facts, I’m tense and nervous, I can’t relax … don’t touch me I’m a real live wire.” And then, in a surrealistic twist, this brilliant stroke of Dada humor—“psycho killer, qu’est-ce que c’est”—and a whole verse in French! New York finally had a song that embraced its paranoia, even flaunted it, but with droll wit.

David Byrne’s character in song seemed to flesh out the specter of Son Of Sam, before we learned that he was just a weirdo named David Berkowitz. FM radio and hip Greenwich Village record shops were the pathway to Talking Heads music and a live culture that I was a smidge too young to take in as a participant. “See ya mom, I’m just heading down to The Bowery to squeeze into a dive nightclub” were not words ever spoken in my household.

A few years later, in college and in the protection of cohorts, I made my first pilgrimage to CBGB, but in ’77, I was still sequestered in the leafy north Bronx, the rock netherworld left to my imagination. Radio fueled that too, as the growing roster of Talking Heads songs found their way across the airwaves. A twist of the antenna brought in scratchy WLIR from Long Island, where whispering hosts spoke conspiratorially about the strange, three-headed bands breeding in the New York underground. The Gotham FM powerhouses gingerly embraced Talking Heads and the burgeoning New Wave: a WNEW-FM host could be counted on to make clever connections with established music, maybe even follow the Heads’ industrial cover of “Take Me To The River” with Al Green’s horn-sweetened original.

In unintentionally hilarious contrast, the plebeian (but more powerful) WPLJ placed Talking Heads’ breakout songs on a rotisserie of incongruous musical contrast with the likes of Linda Ronstadt, The Eagles, and James Taylor—a juxtaposition that only made them sound more subversive. For a few glorious months at the very end of the Seventies, New York got a station fully dedicated to “new wave” as a genre: WPIX. Along with CBGBs congeners Blondie, the Ramones and Television (and with flashes of early rock ‘n’ roll for spice), the brief WPIX format framed Talking Heads within the context of a movement, not as invaders crashing the middle of the road.

One of my most vivid radio listening memories was hearing the spectacularly abrasive Lynn Samuels premiering Fear Of Music on her WBAI show. The public station was conducting a pledge drive and she was baiting the audience with a track-by-track play of the record, broken by fundraising pleas in her inimitable “Noo Yawk” speaking voice. “Oi haaave the noo Tawking Heads album right heah, and Oi’m not playing the next sawng until those phones ring,” crowed Lynn. Ring, they did, and so did the songs that followed.

From “I Zimbra” through “Mind,” “Cities, “Life During Wartime,” quintessentially New York music got a distinctive New York frame. At the close of the “Me Decade,” this battered city of burning South Bronx, raging Brooklyn, Archie Bunker Queens, and faded glory Manhattan came into crystal focus with Fear of Music, arguably the last great album of the Seventies, or the first great album of the Eighties. The album was recorded in a loft in Long Island City a full 30 years before gentrification and that speaks volumes for Talking Heads as “early adopters” of what would become the new cool.

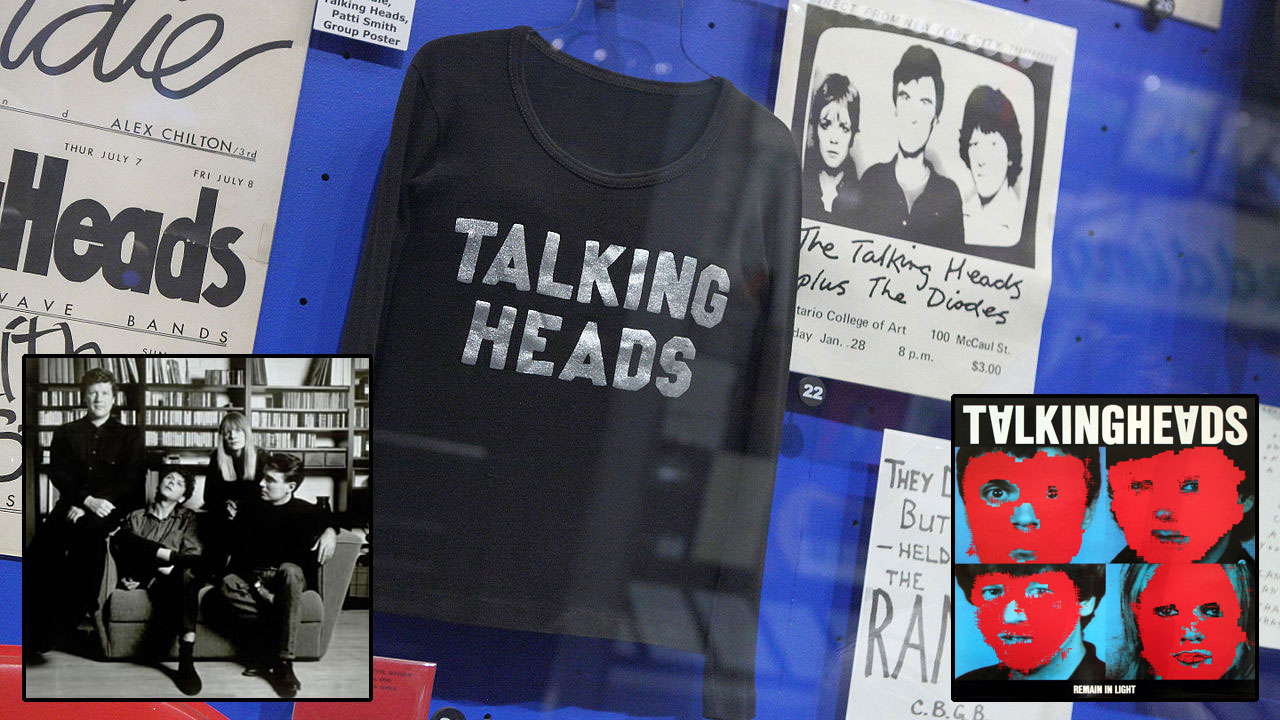

I would very shortly become a participant in the broadcasting world that ignited my passion for music, thanks to WFUV. I recall the excitement of tearing open the Sire Records mailing carton that carried Remain In Light to the station in 1980. That the god-like Brian Eno could collaborate with these scions of the New York avant-garde was a miracle, and the music delivered. In particular, “Once In A Lifetime” sits in a rare class of transcendent pop records that will survive as art songs to communicate the twentieth century to future cultures. Without nailing any specifics, the song’s collage of imagery and references capture an on-the-cusp relief that the Seventies finally ended and the brave new world was positioned to dawn—unless, it all turned out to be “same as it ever was.”

Speaking In Tongues turned an important corner in 1983, with the ascent of “Burning Down The House” to the top of Billboard’s Hot 100. The advent of MTV, and the Heads’ music video for the song brought the big-shouldered David Byrne, Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth’s jaunty groove, and Jerry Harrison’s kindling acoustic guitar lick to the small screen. The big screen too, with the release of Jonathan Demme’s documentary “Stop Making Sense,” and new plateau of stardom followed. David himself would become a filmmaker with “True Stories,” and the band’s accompanying album relaxed into organic textures on some songs. It was tensed enough to string up one more indelible hit with “Wild Wild Life,” and pointed toward separate directions soon for the four singular members.

By 1990, as Talking Heads original incarnation started to wind down, the alternative movement they helped to create had nestled into the establishment. Radiohead would name themselves after a Talking Heads song, but their debt to the band that fused musical world-citizenship with street smarts and fierce intelligence runs deeper than the name. CBGB’s former space is now a gallery and boutique; post-punk fashion gets an installment at MOMA, and the era of Talking Heads sets the premise for the current state of the art, as rock now inches through its seventh decade.

In the class of college-radio rock from the late Seventies and early Eighties, Talking Heads graduated summa cum laude, to permanently reside in the realm of modern art.